Welcome to ChangePath’s five-part series on how to decide where to donate effectively. We’re going to go on an in-depth journey through the psychology of donations, the best ways to tell whether a charity is good at what they do, and how to actually give most effectively. The articles will cover:

- What drives donations

- Choosing a cause to support

- Good ways to choose a charity

- Bad ways to assess charities

- The best ways to give

ChangePath exists to help people make decisions about where to donate. But where to donate is a surprisingly complex question. To truly understand it, we need to dig deep into psychology, the nature of suffering, and the intricacies of the world we live in.

On the face of it, deciding where to donate seems relatively straightforward:

- Choose a cause,

- Pick the best charity within the cause,

- Give them money.

Of course, nothing is ever quite that simple. Do most of us sit down and think deeply about the charities we donate to? Does the average person do hours of meticulous research before deciding on exactly how to allocate their charity budget for the year? Of course not. That’s not really how people work. So how do we actually decide where to donate?

Why we donate to anything

From a completely dispassionate point of view, the fact that we donate at all is somewhat odd. Why give money with no expectation of return? Economists and psychologists, who spend their lives attempting to understand why humans behave in completely baffling ways, have a few theories. When you break it down, there are two different questions – why do we give at all, and why do we give to the specific causes we do?

Why we give at all

There’s a lot of research exploring why we behave altruistically. The simplest explanation, and one that holds a fair amount of weight, is that giving simply feels good. Professors Elizabeth Dunn & Michael Norton found not only did people who gave away money feel happy about it, they felt happier about spending $5 on someone else than spending up to $20 on themselves [act_tooltip title=’1′ content=’ https://www.forbes.com/sites/camilomaldonado/2018/07/10/you-should-budget-for-charitable-giving-even-if-not-rich/#6e3deab17439 ‘]. There are a number of other studies that have shown that giving activates the reward centres in the brain.

But it’s not just about feeling good ourselves. We are social creatures. So even when we think our motivations are pure, there’s often a social aspect to our behaviour. We will donate more when we are asked to give by someone we know [act_tooltip title=’2′ content=’https://www.theguardian.com/voluntary-sector-network/2015/mar/23/the-science-behind-why-people-give-money-to-charity‘]. If we see someone give a large donation directly before us, we are more likely to give a larger donation ourselves. This even works if you don’t know the person – having a famous person recommend a charity can dramatically increase donations.

Of course, not everyone has the same motivations for giving. Some are motivated by social recognition – research by economists Amihai Glazer and Kai Konrad shows that donors are most likely to give the minimum amount to get the maximum amount of recognition (e.g. if you need to give more than $1,000 to be a ‘Gold’ sponsor, most people in that category will give exactly $1,000) [act_tooltip title=’3′ content=’ https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/october-2005/the-economics-of-charitable-giving-what-gives‘]. They say this suggests that people donate partly to signal their wealth.

Yet many people donate anonymously or feel uncomfortable when their donation is announced, so that can’t be a motivating factor for everyone. Indeed, research has shown that wealthy people give for different reasons to everyone else, based on their personal beliefs. Wealthy people were more likely to donate when the ad emphasised what an individual could do, rather than a collective call to action [act_tooltip title=’4′ content=’https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/wealthy-people-give-to-charity-for-different-reasons-than-the-rest-of-us/ ‘].

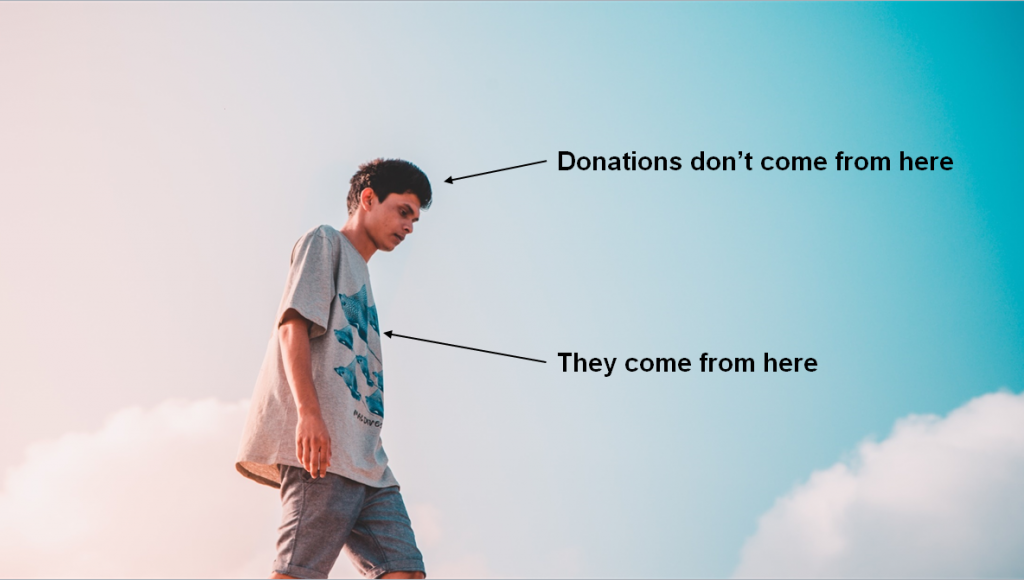

You’ll

notice a common thread – none of these reasons for donating are particularly

rational. Donations are, by and large, emotional decisions.

Why we give to the specific causes we do

Because donations are driven by emotions, the way many people choose which cause to donate to aren’t particularly rational either.

For more than 85% of charitable donations, people donate simply because someone asked them to. Which makes sense given what we know about the social motivations of giving – it seems like we are far more likely to be altruistic when someone else can see it or we have a friendly face to acknowledge it.

But it’s not just that many people aren’t intentional about their giving. No, it’s far weirder than that. Because we give based on emotions, this has a huge number of odd flow-on effects, including:

- Charities that show a single, identifiable beneficiary (often a sad child of some type) get more donations than those that use statistics about the problem. People know, intellectually, that saving many people is better than saving one person. But donations are emotionally driven, so the less people you have on your poster, the more likely people are to donate. Indeed, researchers found that adding one more child to the poster reduced the amount of money given [act_tooltip title=’5′ content=’https://www.thebalancesmb.com/why-donors-dont-give-2502028‘].

- The more futile a problem seems, the less people will give, even if you’re helping the same number of people. When people are told they can save 1,000 people, whether they donate is dependent on what proportion of the overall group they can save. The higher the percentage, the more likely they are to donate. For instance, people were more willing to donate if they could save 1,000 out of 5,000 people than 1,000 out of 10,000, even though you’re saving the same number of people for the same amount [act_tooltip title=’6′ content=’https://www.thebalancesmb.com/why-donors-dont-give-2502028‘].

- Thinking about money decreases altruism. When researchers prompted people to think about money (by, say, having inexplicable monopoly money on the table) they gave less money than those that didn’t [act_tooltip title=’7′ content=’https://www.thebalancesmb.com/why-donors-dont-give-2502028‘].

But here’s the real kicker, especially for those of us who are trying to drive more effective donations.

Advertising which emphasises how effective a charity is does not increase giving. Indeed, evidence suggests that the effect of this information can actually be the opposite [act_tooltip title=’8′ content=’https://www.theguardian.com/voluntary-sector-network/2015/mar/23/the-science-behind-why-people-give-money-to-charity‘].

So charities that base their campaigns on how much impact they have will actually get LESS donations than those that don’t. Indeed, there is some evidence that charity impact scores are used by donors as an excuse not to give, rather than a reason to justify giving [act_tooltip title=’9′ content=’https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Publication%20Files/charity_metrics_v9_d4870581-e84a-4f26-abc7-abf7581fd233.pdf ‘].

And yet, this flies in the face of what donors actually say they want. Donors are constantly asking for a better understanding of the impact they have. Research shows that two-thirds of donors say understanding their impact would influence them to give more [act_tooltip title=’10’ content=’https://www.fidelitycharitable.org/about-us/news/study-finds-donors-want-to-give-more-to-charity.shtml‘]. But it doesn’t.

What’s the conclusion to all this? It’s that the reasons that people donate, and the drivers to get them to donate, are emotional and complex.

Let’s bring it back to the original question – how should you, personally, decide where to donate? If you are to donate wisely, you should be aware of your own mental biases and try to overcome them. Are you looking at charity ratings as a way to talk yourself out of donating? Then don’t. If you want to put a lot of thought into where to donate, then you should.

The core belief that underpins donations

Beneath all of the superficial reasons for donating, there is a single truth. One thing that we must believe in order for us to donate at all.

We donate because we believe that we can change the world with our actions.

We donate to causes we believe can bring the world closer to what we believe it could be.

Donations are an intensely personal choice about what you want to accomplish in the world. How you think the world is broken, and how you think it should be fixed.

In our next article, we’ll talk about exactly how to use that motivation, and the experiences that you’ve had, to choose a cause to donate to.

A fair few of us also give as an expression of faith, putting into effect that which we profess. That starts some of us off, anyway. But we derive similar benefits. Two things I really look for in a charity are integrity and effectiveness. So I like Ozharvest, for example, and St Vincent de Paul society. What puts me off (or tends to) are weepy ads that I consider emotionally manipulative. The WWF ones about starving abused bears or the dying children ones by Save the Children on the box are a good case in point. And lastly, I’m reluctant to donate to what I believe (rightly or wrongly) to be essentially lost, futile causes.